We apply insights from the behavioral sciences like psychology and behavioral economics to public health interventions.

Our research has focused on the communication of nutrition information, portion size policies, and the use of psychological interventions like healthy defaults.

To learn more, check out the textbook Behavioral Economics and Public Health, co-edited by Dr. Roberto and Dr. Kawachi. It is designed to arm public health students and researchers with an understanding of behavioral science theories and how they can be applied to public health research and practice.

Food Labeling Research

Restaurant Menu Labeling

Restaurant Menu labeling is a national policy that requires chain restaurants to post calorie information on their menus and menu boards. The goals of menu labeling are to inform consumers, encourage people to make healthier choices when dining out, and motivate the restaurant industry to offer healthier options.

Does restaurant menu labeling change behavior?

We have written several reviews on restaurant menu labeling that find that calorie labeling’s impact on consumer purchases is mixed. Calorie labeling can encourage some consumers in certain settings to order fewer calories.

Restaurants have been providing nutrition information in stores, why did we need menu labeling?

Our research found that only 6 out of 4,311 people looked for nutrition information in restaurants when it was only available on a poster or as a brochure, suggesting that making it more visible on the menu would help consumers access the information they need to make informed choices.

What type of design features might increase the influence of restaurant menu labeling?

Our research suggests that the influence of restaurant calorie labeling can be increased by adding a label to the menu that recommends adults should consume 2,000 calories daily.

Sugary Drink Warning Labels

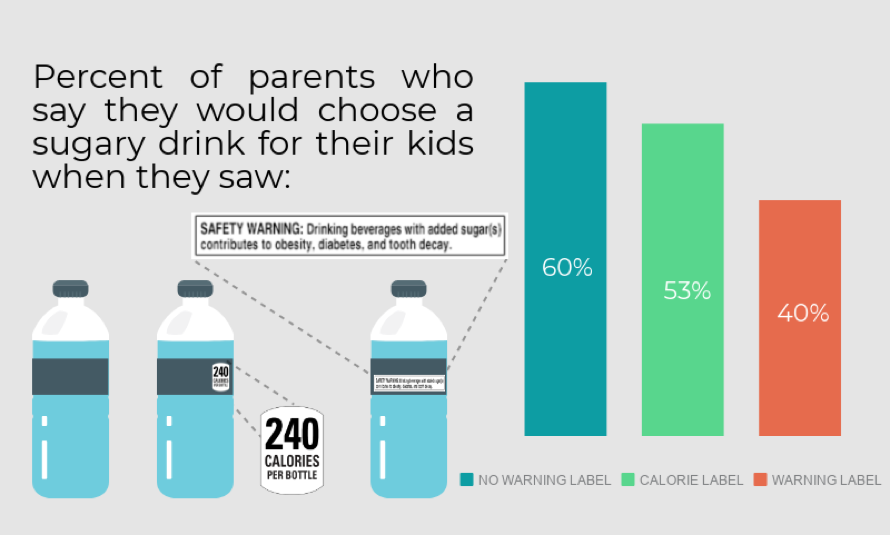

Globally there is interest in requiring health warning labels on sugary drinks, but there is limited evidence on the influence of such policies.

Do sugary drink warning labels discourage purchasing of these drinks?

We have conducted studies to understand the potential impact of this policy on parent and adolescent beverage choices.

Methods

We conducted two online experiments examining hypothetical beverage choices parents would make for their children and adolescents would make for themselves. Participants were randomized to see beverages with either no labels, calorie labels, or a warning label.

Results

We found that warning labels significantly decreased the percentage of parents and adolescents choosing a sugary drink, and helped to educate parents about the health harms of these drinks.

Implications

More studies are needed to understand the influence of warning labels on behaviors, but these initial studies suggest they are a promising policy option to explore.

Front-of-Package Food Labeling

There is increasing global interest in implementing uniform labeling systems on the front-of-packaged foods to alert consumers to healthier choices.

We have conducted several studies that suggest that more intuitive, traffic light labels, which use red, green, and yellow symbols to alert consumers to low, medium, and high levels of different nutrients outperform numeric-based systems.

Our analysis of a voluntary industry-led front-of-package labeling initiative called Smart Choices found that 64% of the products would not be considered healthy be an objective, scientific nutrition standard.

In a randomized-controlled lab experiment, we found that the Smart Choices symbol had limited influence on perceptions of a breakfast cereal and the amount people ate.

We have conducted several studies that suggest that more intuitive, traffic light labels, which use red, green, and yellow symbols to alert consumers to low, medium, and high levels of different nutrients outperform numeric-based systems.

Portion Size

We are interested in understanding whether portion size policies and interventions can encourage consumers to eat satisfying amounts without mindlessly over-consuming food.

Our recent work in this area has focused on sugary drink portion limit policies, like the one proposed in New York City to cap the portion sizes of sugary drinks served in restaurants to 16 ounces.

Our research found that the policy can be undermined if restaurants offer free refills.

We have also written about the scientific evidence in favor of and legality of such policies.